There are a few different ways to handle translated text in your codebase, but here we’ll cover 2 of the more common approaches; using the full text in your source code, and using translation keys.

⚠️ Note: This is an excerpt from my upcoming book & course about localisation for software developers. If you want more of this kind of content, sign up to the newsletter at l10n.expert to get more excerpts before the full release.

Full text in source code

When developing an application an application with only one language in mind, it’s common practice to put the text directly in the source code as it will appear to the end user.

Let’s take an HTML element with the text “Confirm password” as an example. Even if you’re using a templating language, it’ll likely look like this in the source code:

<p>Confirm password</p>

Most templating languages will allow you to use the return value of a function inline, so we can instead pass the text through as a string to a translation function:

<p>{{ __('Confirm password') }}</p>

This is simple to implement, even in an application that you’re not currently internationalising. One of the major benefits of it is that, when browsing your source code, you can see the exact text inline.

Now the translation function can do whatever logic it needs to in order to return the correctly translated version for the current user. The internal logic of the function is mostly irrelevant here - but typically the function will use a lookup-table to find a translated version of the given string.

return [

'fr' => [

'Confirm password' => 'Confirmez le mot de passe',

],

'es' => [

'Confirm password' => 'Confirmar contraseña',

],

];

However, this pattern starts to break down in a few unfortunate ways that make it a less-than-ideal solution.

-

It is harder to write text in this way than without the function wrapping around it. Quotation marks and apostrophes may need to be escaped inside the string, and longer pieces of text may need to be split up, especially if they run over multiple paragraphs.

-

What happens when you want to update the English text “Confirm password” to something else, like “Confirm your password”? As soon as you make this change, the translation function has no way of figuring out what the translations are, as they’re still using the old English text to be looked up. The same change needs to be made in the translation database and the source code to keep it working consistently.

-

This method is so easy for a developer to do, that they can easily forget to add the English text to the lookup table the translation function uses. If any keys are missed and not added to the translation database, it is much more difficult for the translators to know to translate them - they’ll either need to look through the source code themselves or go through the entire application to find any text that’s still in English.

-

Not every word has a one-to-one translation in different languages - words can change meaning in different contexts.

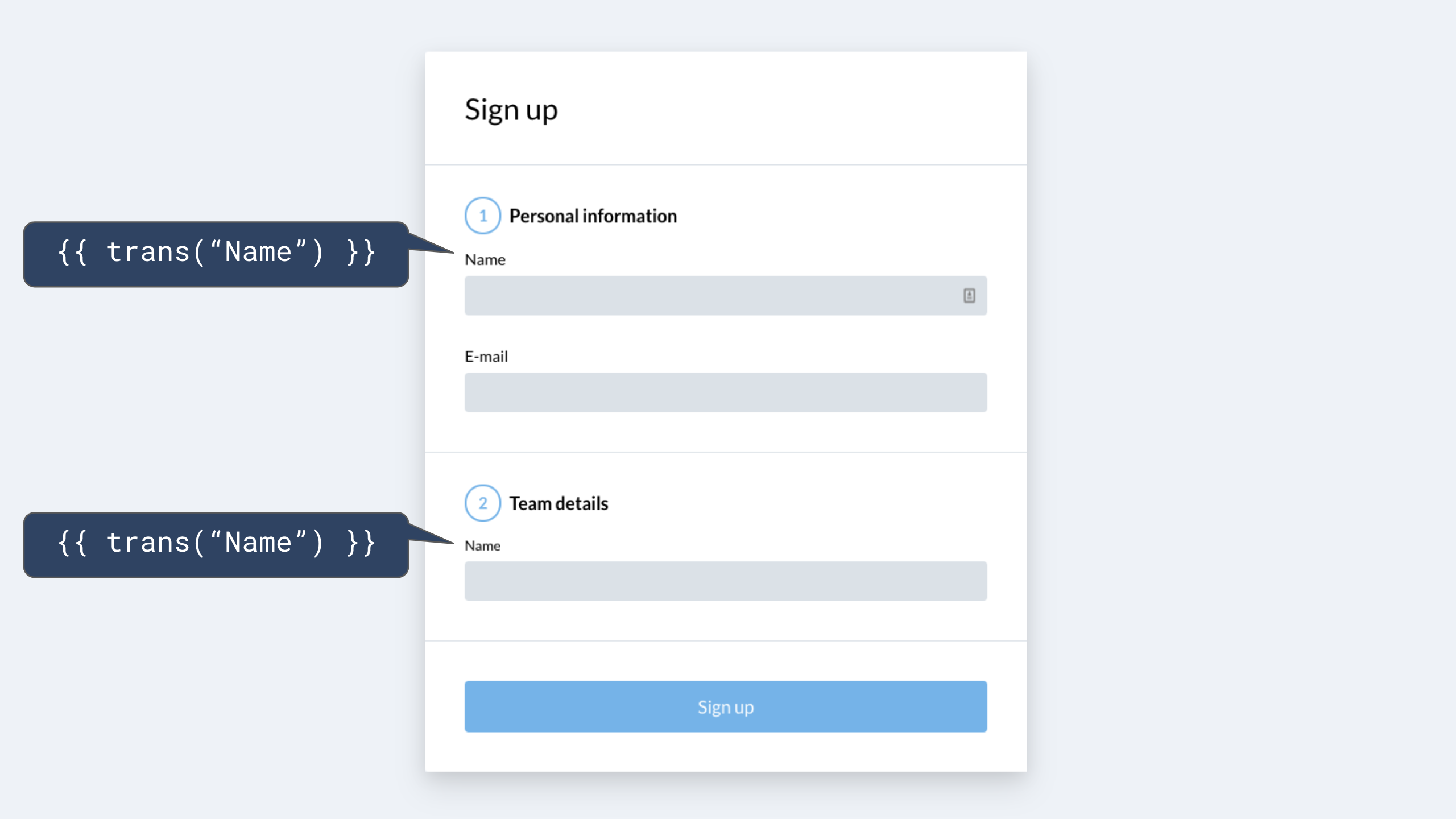

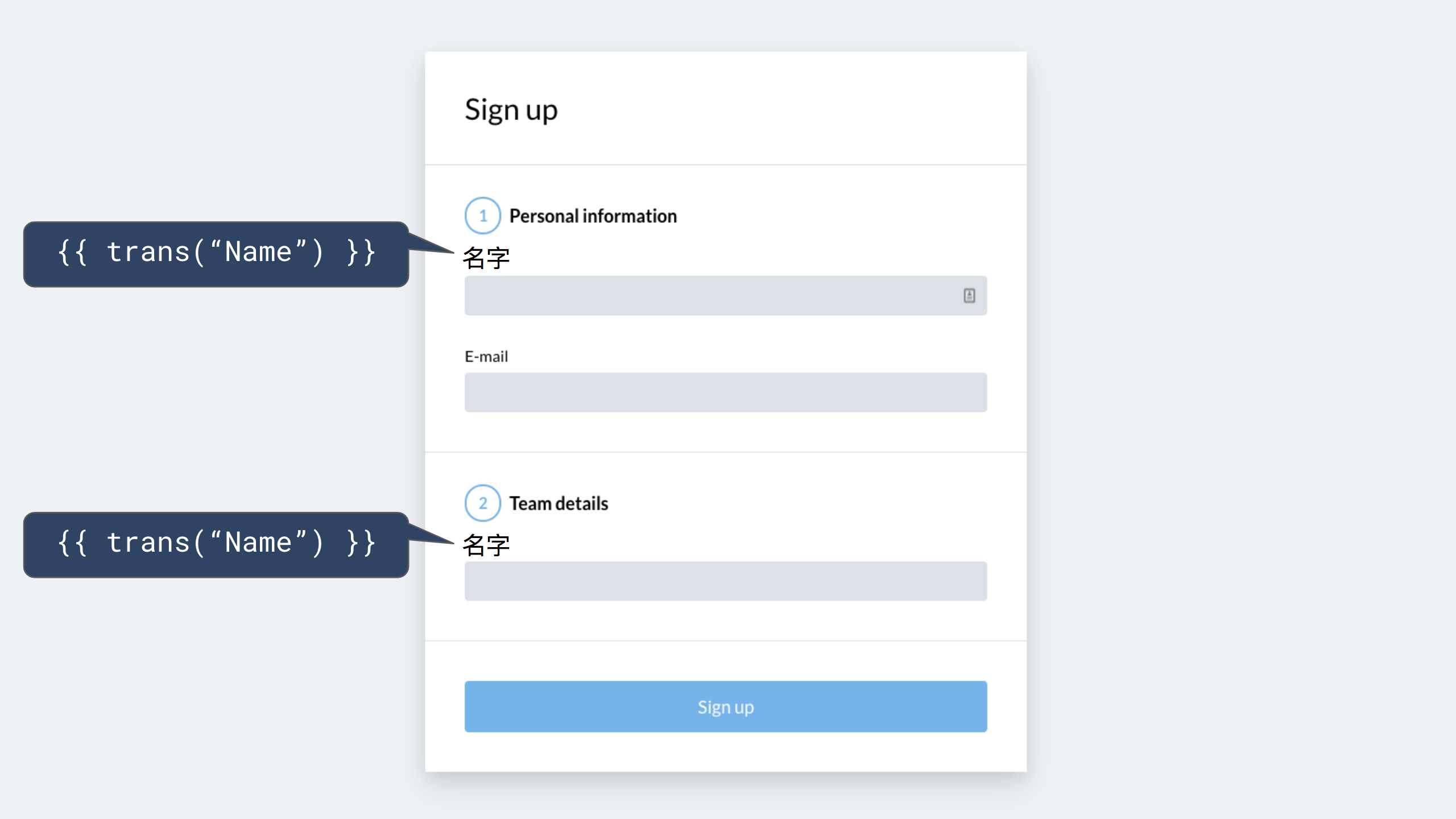

For example, in English, we may use the same word, “name”, to refer to both the name of a person and the name of a team.

However, in Chinese, the direct translation of “name” to “名字” (“Míngzì”) does not make sense in both contexts, and will read improperly and be confusing to Chinese users.

As you can see, this approach does not allow the translator to use a different translation in the two different contexts if they need to, as the source code only accounts for what the text should be in English.

If the same text has been used in 2 places but another language requires different text in one of the contexts, this also means the English text needs to be changed to support that.

As we can see, while this approach may be easy to start off, it’s got far too many flaws that will show up and ultimately slow down development and the localisation process, especially in larger projects.

Let’s explore an alternative solution…

Translation keys

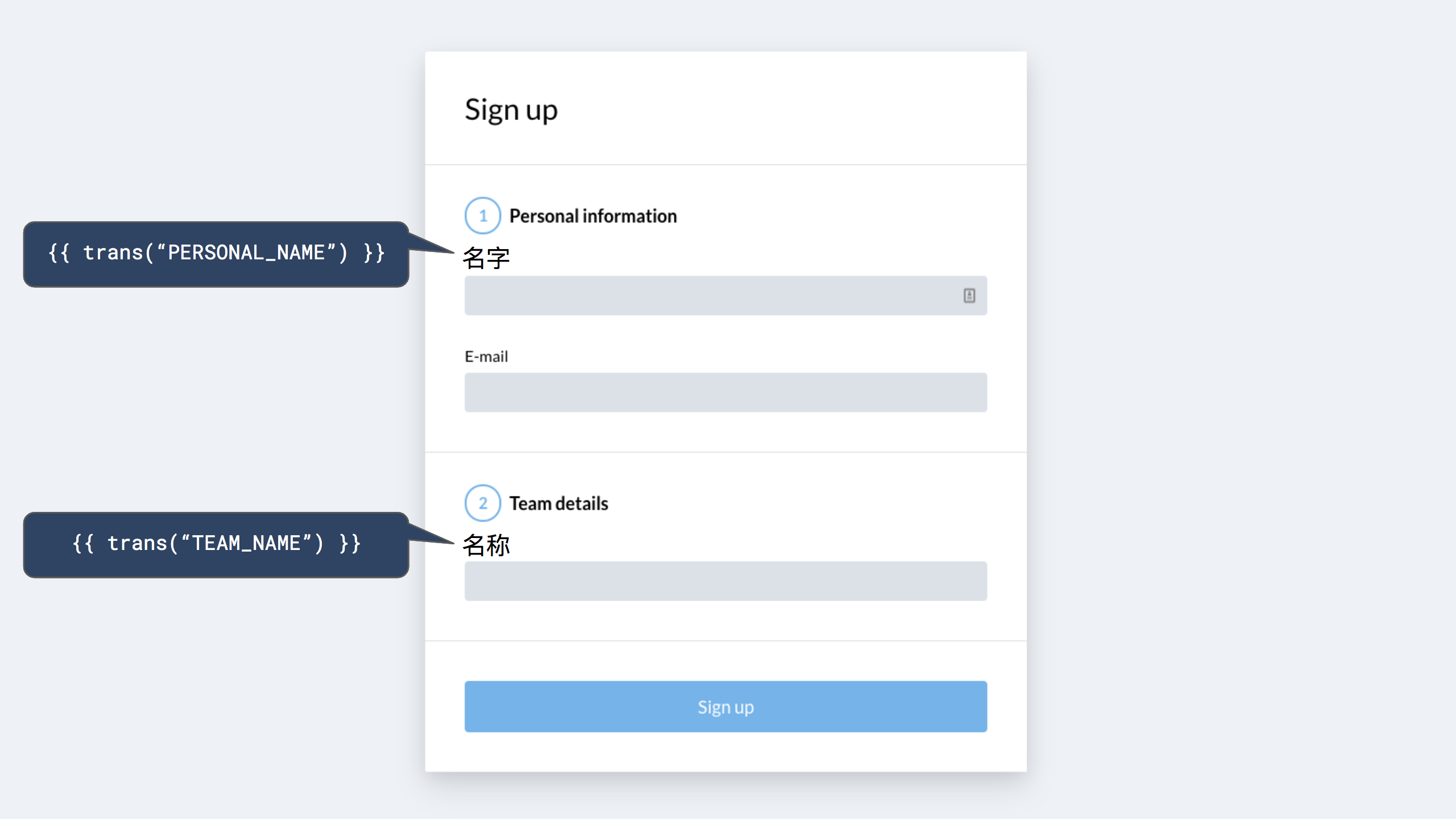

Instead of keeping the base English text in the source code, another approach would be to use “keys” for each string of text that lets it be uniquely identified.

<p>{{ __('AUTH.CONFIRM_PASSWORD') }}</p>

Now we can have 2 entries in our translation database for “personal name” and “team name” when used in different contexts. While the string may be the same for both keys in English, the translator now has the option to use different strings as they see fit.

For example, instead of using the same word for “name” in both places, our Chinese translator can now use the word “名称” (“Míngchēng”) which is more appropriate to represent the phrase “team name”.

return [

'en' => [

'PERSONAL_NAME' => 'Name',

'TEAM_NAME' => 'Name',

],

'cn' => [

'PERSONAL_NAME' => '名字',

'TEAM_NAME' => '名称',

],

];

This approach has some positives and negatives.

The key can ultimately be processed however you want. This can open up additional ways to organise the translations, such as splitting it into categories, or nested objects. One example of this is that instead of using the key TEAM_NAME, you could put it in an AUTH category and refer to the key as AUTH.TEAM_NAME.

Using a key means that the string in the source code is never displayed to the end user. This forces the developer to add the key and real text to the translation database, meaning nothing can get left out and the translation database is always up-to-date with every string used. This does have the adverse effect of slowing down development - as for every bit of text, the developer now has to go to the translation database to add it with an appropriately named key, instead of just using it inline.

It also means that understanding the source code, even when not doing anything related to translations, is harder. As the real text is no longer included in the source code, it gives the developer less context about what a particular template or bit of code might be doing unless they look it up in the translation database themselves.

IDE Extensions & Affordances

However, in most modern IDEs, there are a plethora of tools available to help mitigate this problem for common patterns and frameworks.

For example, in VSCode, the “i18n Ally” extension provides a handful of features to assist in internationalised codebases, such as seeing what the translated text is in different languages for a given key by hovering over it in the source code.

Another nice feature of this extension is that it will display the translated text directly inline in the source code when you’re browsing it and not editing the affected line of code. When your cursor is on a line of code with the translation function, it will display the key as it really is in the source code:

<p>{{ __('auth.failed') }}</p>

But when your cursor is anywhere else in the file, it will display the text from the translation database inline as a visual effect using CodeLens:

<p>{{ __('These credentials do not match our records.') }}</p>

This is hugely beneficial when trying to understand what text is actually used in a codebase, as it takes the cognitive load off of the developer as they no longer have to look up the key manually.

If you use VSCode, give the i18n Ally extension a try to see if it works with your programming language and framework.

As a lot of programming frameworks come with translation support out-of-the-box, there is often additional support for them by their community.

For example, for users of the Laravel PHP framework, the VSCode extension “Laravel Goto Lang” offers a way to immediately go to the key in the translation database just by clicking on it in the source code.

⚠️ Note: This is an excerpt from my upcoming book & course about localisation for software developers. If you want more of this kind of content, sign up to the newsletter at l10n.expert to get more excerpts before the full release.